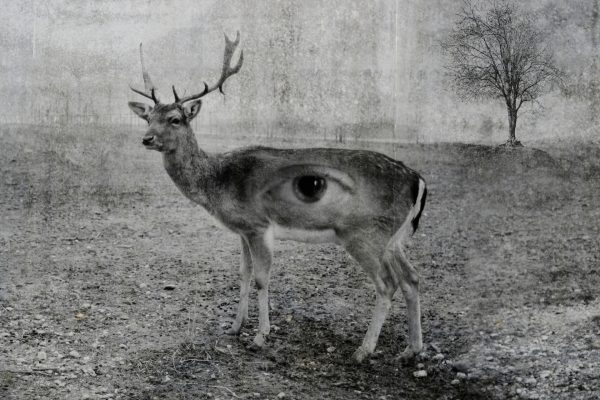

Mickey Strider photographs himself as a dead body in a multitude of dramatic settings, from the profound to the profane. They are desolate, desperate, detached. They are also compellingly beautiful, and impossible to turn away from. They challenge the viewer not just to look, but also to see. They command you to explore the visual space Strider has created. They compel you to discover an explanation for the scene. At the same time, they repel you with their brazenness.

Strider has worked in advertising and film for years, working with big-time names, big-time clients, and big-time budgets. But regardless of how big anything is, he is continually and passionately drawn to the small lens world of still photography.

Strider’s Dead Mickeys inspire repulsion and attraction all in one fell swoop. And the how and why of them is as intriguing as the photographs themselves.

Photography Chronicle caught up with Mickey via Zoom from his home in Atlanta and asked him how the Dead Mickey project first saw the light of day..