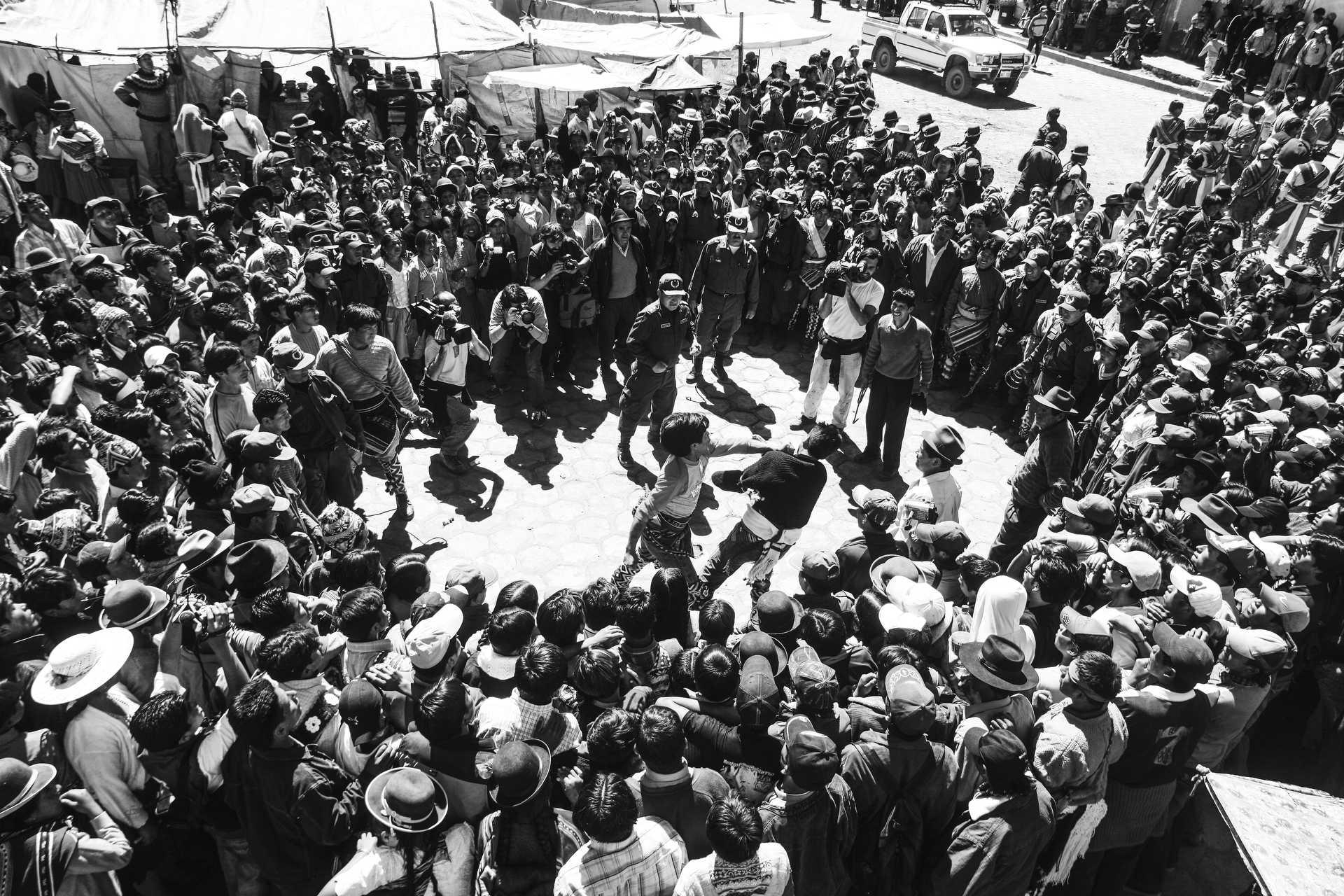

Anarchy in the Andes – Potosi Inka’s gather in Macha for the annual Tinku festival to worship Pachamama – the mother earth.

The Macha Tinku fighting festival in Bolivia is a vibrant and deeply symbolic event that showcases the rich cultural tapestry of the Andean communities. Held annually in the remote highlands of the Potosí Department, this traditional festival is a unique blend of indigenous religious beliefs and ritualistic combat, offering a compelling glimpse into the spiritual and physical dimensions of Andean life. Photographer James Cheadle experienced this firsthand when he was commissioned to fly to Bolivia and photograph the infamous Macha Tinku Festival.

Tinku, meaning “meeting” or “encounter” in Quechua, is a centuries-old practice that coincides with the Catholic feast of the cross in May. This timing reflects a syncretism between pre-Columbian indigenous traditions and the Christian elements introduced during the Spanish colonization. This blending of beliefs is evident in the festival’s dual focus on both spiritual rituals and physical combat.

The religious aspect of Tinku begins with elaborate ceremonies and processions dedicated to Pachamama, or Mother Earth, and other deities. Participants from various communities, or ayllus, gather to offer prayers and sacrifices, seeking blessings for prosperity and fertility. Pachamama is central to Andean cosmology, representing the earth and its bounty, and the offerings made to her are intended to ensure good harvests and communal well-being.

James stayed with some locals in a nearby village for the days leading up to the fighting in Plaza Principal, Macha’s main market square. These days were filled with preparations that included the sacrificing of numerous llamas, and consuming the local homebrew. As he says: ‘it was surreal to be forced to dance around the dead animals while playing panpipes, and being whipped if we dared stop.’ A vivid representation of the festival’s blend of reverence and celebration.